By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

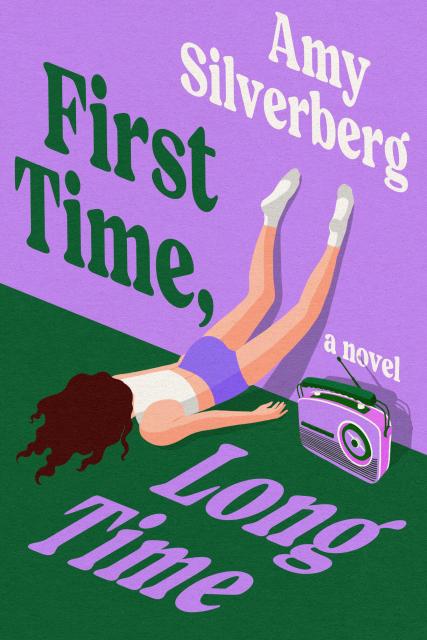

First Time, Long Time

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 22, 2025

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538726495

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

Buy from Other Retailers:

“[T]he funniest debut book of the year.” —Debutiful

For readers of Emma Cline and Melissa Broder, "a brilliant novel about becoming more the person you're meant to be," following an untethered, sardonic young woman who falls for an older man and begins to lose herself (Roxane Gay).

Aspiring writer and all-around naive person Allison expected her life to finally take shape when she moved to Los Angeles. After years grieving her brother’s untimely death and allowing her mercurial father’s feelings and desires to infect her own, she feels ready to become the main character in her own story again. But in LA, as with anywhere else, she’s rudderless, unable to write and barely scraping by as an English teacher.

So when she has a serendipitous run in with famed radio personality Reid Steinman, an idol of her father’s and her late brother’s, she's eager to see where their relationship might go, and who she might become. Caught in his thrall, she falls back into her old self-effacing patterns, struggling to maintain the boundaries of her own identity. Suddenly, an unanticipated lifeline emerges: an intoxicating tryst with Reid's adult daughter, Maddie. She’s forced to balance her romance with Reid with her gnawing desire for the intoxicatingly charming Maddie, as it becomes increasingly evident that she and Allison's late brother share more than a few qualities.

Through candid self-awareness, keen observations, and deliciously wry humor, First Time, Long Time asks, what happens to a young woman’s goals when she becomes involved with a famous man whose needs seem so much louder than her own? And how might she move forward when so much in her past remains unresolved?

Genre:

-

"It’s bold to create a fictional persona with a strong resemblance to the provocateur and radio host Howard Stern. It’s even bolder to imagine a love-triangle between an aspiring novelist, the Stern-esque radio host, and his twenty-something daughter. Amy Silverberg has the wit, insight, and gumption to pull it off."W Magazine

-

"[A] funny, high-spirited novel. . . The book humorously describes a lesser-seen side of Los Angeles: the unglamorous neighborhood of Van Nuys, the shame and humiliations of fame, the agony of trying—and failing— to be someone else, and the thrill of discovering yourself along the way."Oprah Daily

-

"First Time, Long Time uses humor not as decoration but as a coping mechanism, a way for women to maintain some sense of power even when they feel powerless. It’s the kind of voice-driven fiction that prioritizes psychological insight over plot mechanics, asking what happens when we become so invested in other people’s approval that we forget who we are underneath it all."BOMB Magazine

-

"Comedian, writing instructor, and debut novelist Silverberg clearly knows her territory (an author’s note reveals that Howard Stern inspired Reid’s character). Things get complicated, and Allison’s immersion with the Steinmans recalls tensions in her own family unit. But Allison is an able and gifted storyteller, looking back on this time with a kind of awe that she passes onto the reader as she unspools her quiet story with heart, humor, and hard-earned wisdom.”Booklist

-

"First Time, Long Time by Amy Silverberg is the consummate L.A. story. Here is a brilliant novel about searching for answers that can't be found and making grand mistakes and becoming more the person you're meant to be, all held together by the yearning and striving and ambition of any creative person who finds themselves in the City of Angels. Silverberg is a witty, charming storyteller with a bold, unique voice that makes the writing leap off the page and into your heart."Roxane Gay, author of Bad Feminist and Hunger

-

“Amy Silverberg’s First Time, Long Time is not only funny, smart, and tender, it’s also so sneakily well-written that you’ll be tempted to stop to admire a cool turn-of-phrase instead of plowing through to figure out how her f-ed up heroine gets herself out of the mess she’s made for herself. Read it slow or fast - either way, you’ll have a great time."Michael Ian Black, comedian and bestselling author

-

"One of the kinds of books for which I'm most often asked for recommendations is the elusive novel that's smart but funny, literary but still a good time. I can't believe Amy Silverberg's debut novel isn't in everyone's tote bags right around now. Think of First Time, Long Time as this year's Margot's Got Money Troubles, a book that poses big questions with both confidence and a breeziness and that will keep you wanting to turn the pages."The Maris Review

-

“Silverberg packs a punch and gifts readers the funniest debut book of the year.”Debutiful

-

“I didn’t feel like I was reading this amazing book so much as getting to hang out with it every time I picked it up, relaxing into the voice which I savored on every page. Silverberg is a writer’s writer, rewarding us all the time with fresh phrasing that nails an emotional experience, but she’s also a person’s person— open, curious, wrestling with what might be true. A thrilling debut."Aimee Bender, author of The Butterfly Lampshade and The Color Master

-

"From the very first chapter, First Time, Long Time is a charming, enveloping novel about how we obsessively define ourselves through our aching, absurd, and often fraught relationships with other humans. Amy Silverberg writes like an earnest Joan Didion, with dazzling, clear-eyed prose, a blazing, hyper-observant wit, and a heart bigger and brighter than LA County. This is one of the finest literary debuts I’ve ever read. Silverberg’s a massively talented writer. I'm in awe."Dean Bakopouos, author of Summerlong

-

"First Time, Long Time is exactly my kind of funny sad. Silverberg is a master of wry observation. She can be cutting one moment and deeply empathetic the next in her almost surgical understanding of human behavior and the strange comedy of our blundering motivations."Benjamin Percy, author of The Ninth Metal, Red Moon, and Thrill Me

-

"It's a rare book that can balance humor with existential dread, beauty with wryness. Early in the novel, Allison tells Reid Steinman: 'I read at stoplights. I read all the time.' Amy Silverberg's debut novel First Time, Long Time has me wanting to read at stoplights. I felt propelled, sentence by sentence, scene by scene, to read on and on. This is one of the most enjoyable novels I've read in a long time--for its wit, style, vitality, and pizzazz."Olivia Clare Friedman, author of Here Lies

Excerpt from FIRST TIME, LONG TIME

4.

I was sitting at the bar with a book in front of me, when a famous man sat next to me. I’d brought a notebook, but I hadn’t taken it out of my purse. I didn’t have writer’s block so much as writer’s dread. I couldn’t face the pages, their hideous blankness.

“What are you reading?” the famous man asked.

I looked at the cover, suddenly unable to answer. It was a book I read about online, something about magical realism: a father turns into a lamp. I showed it to him.

“Haven’t read it,” he said. “I don’t even know why I asked. I’m not much of a reader.”

I knew immediately who he was, of course. I’d known about him for what seemed like my entire life—as long as I’d known about my parents, about myself.

“I wish I were a reader,” he said. “I know it’s something I should be.”

He was more handsome in person, somewhere in the shallow end of his sixties, wearing a soft-looking black sweater and smelling of expensive soap. I could picture the place where the soap was purchased: one of those quiet, ritzy stores that only sells artisan toiletries, a striking woman at the cash register, a handsome gay man in an intimidatingly stylish outfit by the door. Probably this famous man had never set foot in that store; probably someone else did that kind of thing for him. He sort of looked like one of the monied, liberal dads that sometimes showed up at the expensive private high school where I once worked, dads who drove expensive electric cars and wore hats that said The Future Is Female. Still, those dads showed up a lot less than moms. No-Dad’s-Land, the staff called it, joking.

“I think everyone means to read more,” I said.

“Even you?” he asked.

“Okay,” I said, “not me. I already read a lot. I read at stoplights. I read all the time.” I felt his nearness in my pulse now, speeding it up. I’d heard his voice all my life. All my life, he’d been in the background. I couldn’t figure out a way to say this out loud without sounding absolutely demented.

I’ve been listening to you all my life!

He was the most famous radio personality in the world, the most famous radio DJ to have ever lived. How many radio DJs was he competing with? That wasn’t the point. He changed the form, everyone said that. Also, this man served as my father’s conscience, the cricket on his shoulder forever whispering rights and wrongs. The Problem’s hero. The god of my house. Rather, my father was the god of my house, and he was the god of my father. I’d inherited my father’s gods, just like I’d inherited his knobby knees and an allergy to shellfish.

This man, Reid Steinman, was saying something now, and I asked him to repeat it. Goddamn it. I was a bad listener! The membrane between my thoughts and my words was still dangerously thin. My brother died two years ago. The light in every room still looked changed.

“May I ask what you do?” Reid repeated. I felt struck by the “may”—the politeness, the formality. “For work I mean.”

People in this city were always asking what I did for a living! Even famous people wanted to know! I bounce around, was what I wanted to say. No, “bounce” sounded too easy, too fun. I don’t bounce so much as slide down the wall like something splattered or spilled. But I couldn’t say that— it made no sense! I was having trouble accessing what people said when they met someone attractive, what to say when you wanted to win someone over. “Deep down I’m a good person,” maybe. “I have sex enthusiastically.” These things must be conveyed with subtext of course, but I couldn’t figure out what that subtext might be.

Also, I thought he might be waiting for me to impress him—to make him laugh with the strangeness of my small and singular life. Or maybe ask- ing about my life was just a pickup line, to show that he understood women want to be asked this kind of thing—what do you do, what are you interested in—as opposed to just being looked at.

I’d read that in a magazine profile of him once. He’d said, “Yes, I ask women about their sex lives on the radio, but I also want to know what they do every day, and more so, what they do in private. And not even sexually, just what they do when they’re alone.”

Like a writer, I’d thought, when I read that. Turning rocks over and seeing what’s beneath.

“Before you got here, I was sitting next to someone weird,” I said. I didn’t want to talk about what I did every day. Honestly, I didn’t think I could describe it if I tried. The days passed without my consent. I barely got to look at them. One morning, I kept thinking, I should grab one of my days by the shoulders and look it in the eyes and ask, What’s been happening?!

And what I said was true: I had just been sitting next to a weird man. He left only moments before Reid sat down. This man tapped me on the shoul- der to show me his phone, more specifically an Instagram account, which depicted an Asian woman grilling what looked like a skewer of hamsters on an outdoor flat top grill. He laughed when I recoiled.

“Isn’t the world crazy?” the man said.

I wasn’t sure what he found crazy: that people grilled hamsters in an Asian country he surely hadn’t bothered to learn the name of? Or the fact that he had access to that knowledge—a video of it!—at a bar?

I’d just said “huh” and looked back at my book. I’d been trying to shut the door on the conversation. I always wished I looked like the kind of woman a man might be intimidated to talk to at a bar. Instead, I looked like the kind of woman to whom strangers on airplanes often told secrets. “Approachable” is probably the word.

Reid nodded and I felt embarrassed at letting the story of the weird hamster man spill out like that. I need to talk to more men, I thought. I need to practice talking to men.

Now Reid wore a puzzled expression, as though I might have some- thing on my face—an eyelash or a stray piece of dryer lint.

“I’m glad I came and saved you,” he said. “I don’t normally have such impeccable timing.”

I knew without a shadow of a doubt he wanted to sleep with me. Even if you are a woman whom not every man wants to sleep with (maybe only some men, maybe even only a fraction of them), you still knew this look. You are born knowing.

And listen: I do not think most men want to sleep with me. But some— some definitely do. And yet, the way he was looking at my face—closely, not lecherously—felt intimate, rather than invasive. I’d always found the idea of being with an older man a little sinister. Don’t older men want to control you? Or was that just a leftover scrap from something my mother had said?

Meanwhile, I’d never dated a bald man; had never even slept with one. I’d turned twenty-eight just last week.

“And what do you do for work,” I said suddenly. I’d pretend I had no idea who he was. It felt good to render him anonymous, like I’d grabbed a little power back.

“I’m on the radio,” he said. “You have a radio show?”

“Yes,” he said. “I have a show. I’ve had it for a long time.”

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Reid,” he said. He stiffened a little, having to say his name in a bar. “Reid Steinman.”

“Reid Steinman.” It was a thrill to say his name back to him, right to his face. I repeated it slowly, as though I were sounding out words in a different language. Then I said it again. “Reid Steinman,” like it was suddenly becoming familiar to me, lyrics from some long-forgotten song. “I think my dad’s a fan.”

He smiled. “Is that good or bad?”

“Neither,” I said, though I couldn’t decide if that was true. “I think he listened to you when I was growing up.”

“A lot of dads like me,” he said.

I could picture these dads, on the other side of the proverbial hill, saggy-faced and beer-drinking men who liked to hear a dirty joke in a bar. But I knew that was only a stereotype. If I knew anything about dads: They were complicated.

Reid smiled again, but there was a tightness. Maybe this was a tired ritual. How many times did he have to sit and listen, his face as open as a menu, while a fan recounted the many hours they spent listening to him growing up, or their parents had. Or maybe this felt exciting to him, the way something you were good at—that always ended well for you—was exciting, like teaching sometimes was for me. Like writing used to be. I didn’t want the conversation to end and suddenly I felt very worried about what I might say next. I wanted to extend the moment. Surely it was just a moment. I thought around for something to say.

“Do you have any kids?” I said. I knew he had one. He almost never spoke of her on the radio. When he did, it was only in passing: I visited my daughter in college. Oh, my daughter plays the guitar.

“I have one,” he said.

I knew from listening to the show for so long that his family was off-limits. And maybe his daughter would’ve been, had he known I was a fan. But luckily I wasn’t. I was just a girl in a bar.

“And what does she do?” I asked.

“She’s in between things,” he said. “She’s back from college.”

I wondered how old he was. My father’s age? I’d google it as soon as I was alone. He looked sort of ageless, in the way well-tended bald men sometimes look, shiny and smooth and elaborately moisturized. In the dim, buttery lighting of the bar—beneath those stylish naked bulbs I some- how associate with lonely geniuses—his edges appeared softened. It was romantic comedy lighting. There was a doglike quality to his face, a sort of turned-up nose, like a pug. But he was not unattractive. Probably he had spent a lot of time looking at himself in the mirror, at different angles, in different clothes—testing, trying. And so much could be improved with money! Could be massaged and papered over. Had he gotten plastic surgery? I’d google that too.

“So your father listens,” he said. “But you’ve never heard me?”

Of course my first instinct was to continue to lie. Lying had always been my first instinct, for as long as I could remember. Something to do with my dad—I’d take any pains to hide a truth that might upset him. But where had my instincts gotten me? And what could I lose from telling the truth? Dignity, maybe, but I didn’t have that much dignity to start with.

“I’ve listened before,” I said.

“A casual listener,” he said.

“Something like that.”

“So you do know who I am.” He raised his eyebrows in an exaggerated way. I remembered he played a role in a superhero movie once, as a bank teller, but he wasn’t very good, and had never been cast in anything again.

I kind of liked that he’d already caught me in a lie, at least a small one.

He’s getting to know me! I thought.

“I know who you are,” I said. I grinned, like I’d wanted him to find me out.

“Good,” he said. “If you didn’t—” He touched his head as though miming a headache. “It can be difficult to explain.”

The bar was uncrowded, but I could feel the static of other people’s eyes on us. Uh-huh, someone whispered, that’s him. A few people craned their necks to look. But at other tables nobody cared. Life in this city went on: a script was purchased, a dream was crushed. “That was her fourth affair!” someone shouted, to an eruption of laughter. I was always getting distracted by other people’s lives.

“I’m a teacher,” I said, “in answer to your earlier question.” I liked how noble it sounded, and humble too. I wanted to help people! I did not mention the other strung-together jobs: the horoscope app, the lingerie website, the book clubs. Then, I thought I noticed some slight change in his face: a droop- ing around his mouth. Teachers were boring. They did not do, and that was why they taught. “I’m a writer too,” I said and immediately regretted it.

“What have you written?” he asked.

“Nothing you’ve read,” I said. And if he knew that meant things had not gone well, writing-wise, he didn’t show it on his face. “But I’m working on something new,” I lied.

“I’d love to read it,” he said.

“Maybe someday,” I said. I meant it: I found the whole idea of him reading something I wrote terrifying and exciting both. I might even say arousing.

“And do you like teaching?”

I was not used to being asked so many questions, to being the center of someone’s attention. “Yes, well. Yes, I do. But sometimes I wish I was doing something else.”

He smiled, and I noticed his teeth were unnaturally white and straight. Capped? Veneers? These were things I hadn’t known existed until recently. I’d moved to Los Angeles one year ago, after I’d gotten tired of the private high school where I worked up north. (I liked calling it that: up north. It made me feel like I was a frontierswoman, or an explorer.)

“There are a lot of things you don’t know,” an ex-boyfriend had said, “for someone who reads so many books.”

“What else do you wish you were doing?” Reid asked now, flashing his much younger teeth.

“At this moment?” I said. “Nothing.” I was flirting now, leaning closer to him. It was trite choreography, but I was relieved I remembered the steps.

“Instead of teaching,” he said, but he was leaning closer too. “Did you always want to be a teacher?”

No, I thought. “Sort of.”

“I sort of wish I’d done something else,” he said. “I guess that’s easy for me to say now, right?”

A man approached from behind Reid, and I wasn’t sure if I should say some- thing. I liked the idea of giving Reid some sort of signal: like we were on the same team, two people colluding. The guy was middle-aged, in a baseball cap, its brim optimistically stiff. Before he reached Reid, he turned the cap backward in one fluid motion. When I first moved to LA, I couldn’t believe how many of the men wore backward baseball caps and frequently asked for help.

“Are you from the Midwest?” a coworker had asked when I’d said this.

“No,” I’d said, “I’m from the middle of nowhere,” which wasn’t really true. Of course it wasn’t true—everywhere was somewhere, but I was from somewhere very specific: outside of Reno, Nevada. The town has a name but I won’t use it. The whole place still feels difficult to explain, in the same way it is difficult to explain the taste of food, or your own childhood.